How did the database project begin?

The Manart project began in 2012 during the seminar entitled “The Artistic Manifesto: A Collective Genre in the Era of the Individual,” organized at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). An initial database that brought together artistic and literary manifestos of the twentieth century from France and rest of the world, was presented by Camille Bloomfield. Shortly afterwards, the team was created with the two seminar organizers, Viviana Birolli and Mette Tjell, and one of the participants, Audrey Ziane, all of whom were already working on the history and evolution of the manifesto in art and literature.

The project first received support in principle from the Centre Hubert de Phalèse (part of the laboratory Écritures de la modernité, Université Paris 3) specialized in relationships between computing and literature, and from the Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage (CRAL, EHESS), a laboratory favourable to sociological approaches of arts and literature. For three years, the four researchers involved in the project worked without any institutional subsidy. It was only in 2014 that the Laboratoire d’excellence “Création Arts Patrimoines” (Labex CAP) granted funding for the project for one year, which enabled the computerized development of the database and its publication on the basemanart.com website with the help of programmers and web designers.

Today, the project is supported by the laboratory Pléiade of Université Paris 13 in Villetaneuse, to which Camille Bloomfield is attached, and by the “Délivrez-nous du livre” (“The Book After the Book”) federative project at the same university. It continues to evolve technically and scientifically within this framework, particularly with the Atelier Manart (Manart Workshop), a research seminar supported by the Campus Condorcet, which took place from January to June 2017 in Paris. Now, thanks to this workshop and to the collaborative nature of the website, the project welcomes a community of researchers open to enriching the database according to their disciplinary or geographical specialty.

The Manart database records manifestos produced worldwide in the twentieth century in every area of creativity. Continually under expansion, the database included 725 manifestos as of 1 April 2017. Information that is both descriptive and analytical collected in the database allows searches that contribute to the expansion and nuancing of analytical perspectives of the manifesto as a genre. Which part of the manifesto was made individually and which collectively? Did it experience a “golden age,” as is often believed? Where are most manifestos produced? Which media were privileged by artists to communicate their programmes?

How was the corpus defined?

The question of what the corpus would contain was as passionate as it was complex to resolve. As both text and act, the manifesto is a form that is difficult to delimit. To be restricted to a simple definition would be insufficient because that would assume the existence of an ideal type of manifesto – an existence that remains to be proven. Moreover, in the sense that it asserts a new stance in the arts, the manifesto is always conditioned by the state of the artistic field in the era of its publication and takes on a vast variety of forms and discourses. In view of this, how can such a fluid and “undisciplined” genre be systematized?

In order to be included in the database, each document must meet at least one of the following three conditions: 1) include an explicit assertion of belonging to the manifesto genre (“manifesto of…” or “for a …,” etc.); 2) correspond to a general definition of a manifesto;1 3) have been accepted as a manifesto by at least one specialist in the field.

These three criteria don’t only serve to determine a corpus. The advanced research engine also allows each user to conduct searches by determining his or her corpus in terms of his or her research objectives: if s/he interested in the dynamics of the artistic field, a large selection is preferable because this allows the inclusion of, for example, non-collective texts that express an individual stance. If, on the other hand, s/he is wondering about the definition of the manifesto, a more limited selection is interesting, in the sense that it makes a study of the evolution of the genre’s distinctive traits possible (Bloomfield & Tjell 2013).

Determining the chronological framework of the database was another major challenge. A starting point was set at 1886, the date of publication of Jean Moréas’s “Symbolisme,” in Le Figaro, which led to a wave of manifesto productions emanating from groups of poets and artists. The Manart database does not propose an end date, so that the team is able to follow the evolution of the genre over time and consult its most recent forms.

The country of production and the disciplinary field to which the recorded manifestos belong are not restricted in any way. Including manifestos relevant to all artistic disciplines and all geographical areas allows, in particular, evaluation of the transdisciplinary and transnational nature of a movement, and comparison of the discursive and definitive characteristics of the manifesto from one discipline and one country to another. Is the manifesto not the only genre which artists and theoreticians of all creative fields have seized upon? Two variables which can be cross-referenced have therefore been adopted: the country in which the first version of the manifesto appeared and the language in which it appeared.

Which software programs were used to build the database infrastructure and, as the case may be, to treat the data statistically?

The Manart database was first developed using a standard spreadsheet (.xls format), and then converted into XML for its online publication on the project’s first website, built using Joomla. In the end, the Drupal platform was chosen for the second version because of its broader range of technical possibilities. The database’s entries are therefore Drupal “content,” linked to a database in SQL format.

An integrated research engine enables detailed searches in the content, while standard pages offer the project’s research protocol, history, and project-related news items. In order to allow collective use, only registered users can propose new manifestos or suggest changes to existing entries.

The next worksites under consideration are: display of visual contents for entries (facsimiles of the manifestos); OCR processing of the texts themselves to enable full-text searches, and the export of research results associated with data display tools (statistics). For now, only the project’s team members can have access to statistical treatments of the results.

Could you offer one or two examples of scientific (whether consensual or surprising) results obtained with the help of the database

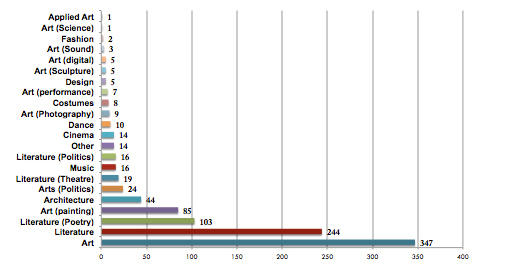

In so far as this platform tends to erase the distinction between seminal historic texts and others more easily overlooked, Manart privileges approaches that distance themselves from teleological visions of literary or artistic history conveyed by anthologies of manifestos. For example, someone who is interested in the evolution of the genre in the twentieth century within different disciplines could carry out a search on the parameters of the artistic field in the entire database. The “Art” category, which aggregates the majority of the manifestos as shown in the graph below, assembles transdisciplinary manifestos that were particularly frequent in the period of the historical avant-garde at the beginning of the twentieth century. While the graph obliterates this temporal aspect, such a search reveals the impressive interdisciplinarity which makes the specificity of the genre, as well as areas in which evolutions of the manifesto have not yet been much explored – architecture, cinema, and comic strips, among others.

Figure 1. Data retrieved from Manart by C. Bloomfield and A. Ziane (29 March 2016*)

*The field of appearance was the variable used. Several fields correspond to one manifesto, hence the impossibility of expressing these results as a percentage. The database contained 725 entries at the time.

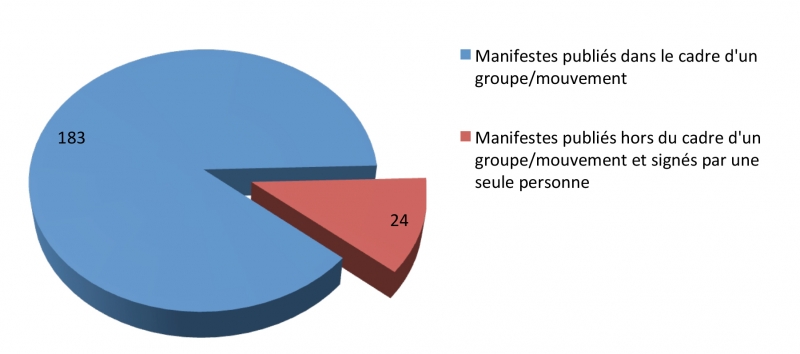

Des recherches peuvent aussi porter sur les propriétés internes du genre : il est par exemple possible de visualiser la proportion de manifestes produits à titre individuel ou collectif, comme le montre le graphique suivant, constitué à partir d’un corpus de 207 manifestes parus en France.

Figure 2. Data retrieved from Manart by M. Tjell (29 May 2016)

In blue: Manifestos published within a group/movement ; in orange: Manifestos published outside of a group/movement and signed by one person.

This graph relativizes the necessarily collective origin of the manifesto by giving a statistical existence to manifestos in the “singular” form, that most critical studies do not take into account. While we can confirm that manifestos produced and issued by individuals represent only 12 per cent of the corpus (24 entries) and therefore constitute a marginal phenomenon, a search by year of their production shows that the majority of these texts were produced as of 1980. This finding, therefore, invites reflection on the adaptability of the manifesto to the socio-economic conditions of its time and on the decline in the twentieth century of collective practices.2

The quantitative research made possible with the database contains certain limitations, however, for the study of the manifesto. Although these methods enhance the range of approaches available to the researcher, the considerable broadening of the body of texts taken into account by the database has a tendency to diminish, if not erase, the actual impact and performative power of each manifesto. Because it tends to assign an equivalent weight to all documents, Manart diminishes, for example, the impact of avant-garde models on the manifesto production of the twentieth century. However, it is difficult to conceive of the history of the manifesto without taking into account the dynamics of influence and the complex intertextual references that link neo-avant-garde manifestos of the 1960s and contemporary recycling of the genre, to their avant-garde “ancestors.” Here, as with most quantitative research, the results offer only a schematic and partial image of reality. While the latter offer the opportunity to ask new questions concerning the use of manifestos and to enhance the understanding of them through new study perspectives, it is advisable to then return, as a specialist in artistic fields, to the texts and works involved.

What plans do you have with regard to the durability and accessibility of the database?

The team wants to make the Manart project into an open access research platform. That is the reason why consulting the database is not dependent on the creation of an account: everything is instantly visible. The addition of digitalized facsimiles of original documents would represent an important step in this direction because it would open the database to new fields and new users.

Currently in its early stages, such a development will require, however, the collaboration and support of patrimonial institutions such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France or the Bibliothèque Kandinsky, particularly for copyright issues and issues concerning the long-term archiving of data. A first option under consideration allows for the redirection towards manifestos already available online and stored within permanent institutions, which would make Manart a sort of online manifesto “hub.”

There is also the question of storage: should it be stored on university or institutional servers, which would guarantee better durability but impose more technical constraints; or should we preserve a degree of autonomy and technical flexibility for the project, which would require other solutions in order to ensure perpetuity?